How can we know what is real? How can we parse wild-eyed theories from deception and then segregate both of those into a far corner away from the truth? Many utilize intuition to parse conflicting narratives, and while intuition may play a minor role in later stages it is wholly inadequate for quick assessments of complex things. I never liked Donald Rumsfeld, but he succinctly described the foundation of design methodology, there are known knowns, known unknowns, and unknown unknowns – there are also things we think we know that are not true. This seems obvious but people often ignore these almost immutable laws of nature.

So if we accept that the world is complex, and that is true even if everyone’s actions matched their words, then we have to accept that there are rules we can apply to understand facts. Of course, not all act in accordance with their words. This only serves to increase the complexity, when we accept that some intentionally deceive and others conspire together to spread deceptions the web of complexity increases exponentially.

Many prescribe critical thinking as a remedy, as a tool to help separate signal from noise and wheat from the chaff. That is inarguably true, but in my estimation, many who remark on the value of critical thinking do very little of it. The term has become a rhetorical device. They will proclaim, “you cannot see my point because you are not critically thinking”.

Here are two definitions floating around about critical thinking.

“The intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.”

“Critical thinking is essentially a questioning, challenging approach to knowledge and perceived wisdom. It involves ideas and information from an objective position and then questioning this information in the light of our own values, attitudes and personal philosophy.”

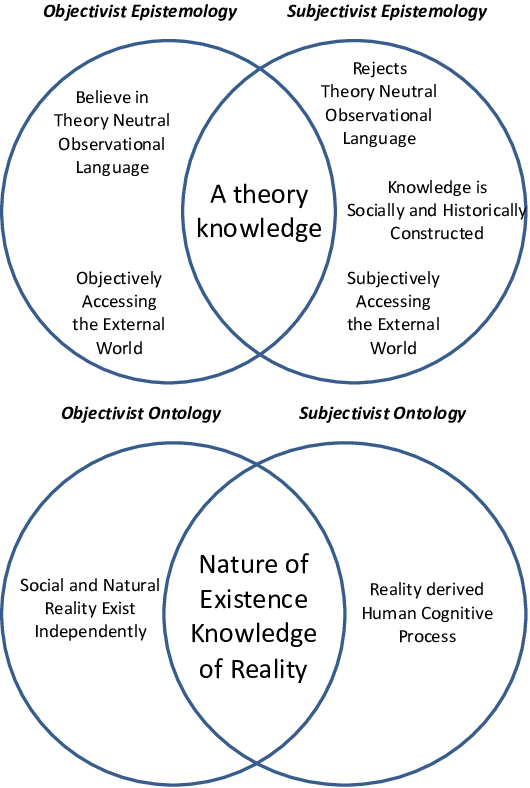

Can you spot the difference? The difference is essentially the same as asking if a person believes ethics exists because truth exists or that truth exists because ethics exists. In the first of each example, a person arrives at beliefs after evaluating information and synthesizing knowledge. In the second they look at synthesized knowledge and then filter that through their personal values and beliefs. The first is objective, the second is subjective. The first can seek to find true answers and the second can never find agreement. The first is rational, the second is irrational.

Irrationality leads to absurdity, and worse. It cannot help one seek understanding and knowledge. Many in our current public discourse use the term ‘critical thinking’ but they do not mean true epistemological understanding. Rhetoriticians use the term to make strawmen of their opponents. The term has little use to us. The concept, however, is useful.

My personal methodology of seeking knowledge and understanding centers on nature of the thing thinking, but I have a process, more or less formal, that I use.

First

Is the problem/question at hand a theological one?

Everything has a theological significance; everything relates to theology. But we might differentiate between a problem that requires theology in its framing and a problem of interpreting and discerning theology. At the end of this article, I have attached some resources that are of assistance in answering questions related to what is correct theology. One ought to not confuse the fact that those items are at the end means they are of secondary importance. Get theology right and most problems of thinking become simpler.

Remember, theology is hard, heresy is easy.

Use First Principle Thinking

Begin your inquiry into any subject, problem or truth claim using first-principle thinking. Apply to each and every thing universal truth before you attempt to discern necessary, contingent, or particular truth related to specific conditions and claims. Work through the syllogisms apparent from the first principles you recognize. Here is my attempt at a top-level list. First Principles, Axioms, and Syllogisms - I never encounter a problem and never evaluate any truth claim, big or small without first connecting that claim or problem to first principles. Remember always that sophists make arguments that are apparently, or seemingly correct using rhetoric but their arguments often fail at the start. This is easier to notice by applying first principle thinking. Use this as a shield to parse fancy words and compelling arguments that are wrong from truth. But be aware, some of the most skilled sophists we find in history we so successful because they use the language of truth and epistemological and philosophical terms in their truth claims - discernment is required to protect against these sorts.

Gather facts and Assumptions

Early on, in any issue, many voices will run with various narratives and explanations. Within those narratives are elements of facts that are true. Often we do not have access to the raw data that was used to create these theories. We are left to sift through the analysis of others. I begin my reading of anything with a simple premise; intent before content. I want to know who the speaker or writer is, what their worldview is, what other things have they said, and perhaps if they have told us at some point, what their intent is. I never dismiss a story because of what I infer the intent might be unless it is from a proven liar or fraud.

So first, attempt to understand the speaker's bias, while suppressing your own, and then dissect the content, looking for truth claims and any evidence that supports those claims. Cross-reference the claims, see what others are theorizing about the claims and check their work. In this way, you will begin to form a mental list of things that appear to be facts and assumptions that have the potential of becoming facts with more evidence.

Check and Recheck Facts

This is an ongoing process, conducted throughout the method. Never be afraid to go back and reevaluate something you marked as a fact if numerous facts contradict each other.

View it Systemically

In a complex world, very few things do not impact other things or are impacted by other events. Facts are no different. If one side of a discussion presents what appear to be valid facts in their argument and the other side too has some facts to support their cause simply pull back from their narratives. Ask how these things might be simultaneously true and therefore disprove both narratives. Is there something larger at play?

Look for Patterns and Coincidences

Coincidences in this case mean something more than something being adjacent. Ask if there is relevance in the adjacentness. Many people create false relations of unrelated facts at this juncture. Much care is required. But real coincidences, especially over time, indicate a pattern. You are seeking to decipher signals in the noise and patterns are signals.

Ask About the Nature of the Thing

If you detect a pattern in the noise and can detect facts that are related, and also have explained facts that at first blush conflict with those facts (a systemic approach) you are on to something. If a series of events occurred, and you can understand verifiable facts related to those events, and you can discern a pattern, then ask what is its nature. Who benefits, who does it hurt, what cause does it further, etc. Understanding the nature of an event or an explanation for an event, girded in an understanding of the facts, very often reveals which truth claims are valid and which are false.

Ask About the Nature of the Speaker

Rhetoriticians are skillful and persistent. In our information age narratives take on a life of near deification. Well-written articles in major publications will be followed by the talking-head news circuits and then onto social media as memes and then simple statements of facts and finally as ridicule –“do you even critically think?” But what is the nature of the speaker, have they demonstrated that they honestly evaluate facts to synthesize knowledge? Do they ’critically think’ objectively or subjectively? Some speakers are so dishonest with an evaluation of facts and so sloppy in their methodology that through their intent they devalue their content.

Synthesize Knowledge

Connect what should be connected, explain rationally what seems to conflict but is not connected, look for other drivers that may be altering the equation unseen, and then form a theory, a hypothesis of knowledge about the thing. There are but a few universal truths, a handful of first principles, and everything else remains subject to our continual revisiting. Our truth claims on these matters are true only as long as unchallenged by new facts.

The loose methodology above does not mean you will always be right, even if you follow it, or a better concept, exactly. You will not follow it exactly, every time, unchecked bais will slip in from time to time. Even a perfect execution of this in praxis still does not ensure always getting it right. Sometimes there are unknown knowns that are undercovered that hold such import they would change your conclusions.

You will seldom walk with any crowd if you apply principles like that to your analysis of the world. In our political divide, neither side will embrace you, or understand. You will be called names by all, dismissed, ridiculed, and shunned. That is the nature of objective truth, it is inconveniently painful to what people want to believe. But truth and understanding are infinitely more valuable than popularity or the applause of men

- image via Edward Sek Khin Wong, DOI:10.5897/AJBM11.1387